Beyond toilets: Managing human waste across the sanitation chain in India

Cover image (c) CSE

In a bid to end open defaecation, India has built more than 100 million toilets since 2014. But to protect human health and the environment, cities have to safely manage what comes out of them. Shit Flow Diagrams have emerged as a key tool to help them plan and monitor progress.

A country drowning in its own waste

A decade ago, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), a prominent environmental NGO based in New Delhi, published Excreta Matters, a seminal study which examined the state of water and wastewater management in 71 cities. Its unforgettable conclusion was that India was a country ‘drowning in its own excrement.’

At the time, hundreds of millions of people in India were still practicing open defaecation, their faeces left exposed in fields or behind bushes, in ditches, or in open water bodies. But this was not the only route by which faecal matter was polluting the natural environment: Leaky sewer pipes, overloaded sewage treatment plants, septic tanks which emptied into open drains, and illegal dumping of faecal sludge all played a role, too. Indian cities were simply growing too fast for their patchwork sanitation systems to keep up.

Sanitation for all requires ‘new technologies and new thinking’

‘The challenge for India is to come up with ways of dealing with excreta that are affordable and sustainable,’ wrote Sunita Narain, the director general of CSE, in the journal Nature shortly after the publication of the study. Current technologies that ‘use large amounts of clean water to transport small amounts of excreta through expensive pipes to costly treatment plants’ are unworkable for India, she argued, not least because of the growing pressure on water resources caused by rapid urbanisation and climate change. She appealed for ‘new technologies and new thinking’ to achieve sanitation for all that ‘does not cost the Earth.’

Shit Flow Diagrams come to India

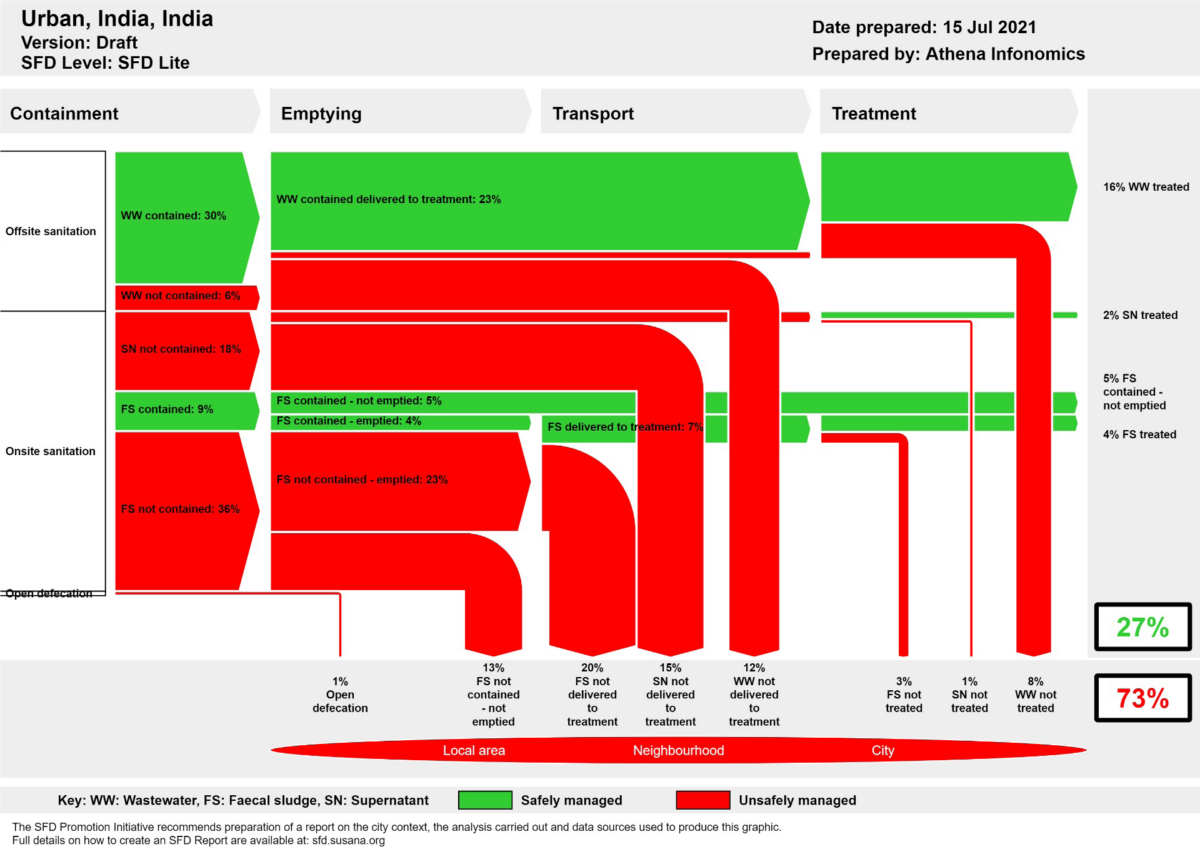

Some radical ‘new thinking’ arrived in India less than two years later, in the form of the Shit Flow Diagram. An SFD is a graphic which visualises how human excreta moves through a city – from the point at which it is generated through to its final disposal or re-use – and the proportions of it which are safely (and unsafely) managed each step of the way.

SFDs were originally developed by water and sanitation experts at the World Bank in 2013 as a tool for analysing sanitation systems in rapidly urbanising areas where the majority of people do not have access to toilets that are connected to a sewer system. The graphics quickly found adherents within the global sustainable sanitation community, a diverse group of institutions committed to promoting sanitation solutions for the 1.9 billion urban inhabitants worldwide who rely on on-site sanitation solutions, such as septic tanks and latrines.

Among these was the Sustainable Sanitation Programme, a global initiative implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). In 2014, Dr Arne Panesar, the head of the programme at the time, approached Sunita Narain and her colleagues at CSE about the possibility of becoming a founding partner in the SFD Promotion Initiative, a new global collaboration managed by GIZ and implemented by multiple partners with co-financing from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

‘The aim of the SFD Promotion Initiative was to set off a series of “controlled explosions” in the sanitation sector,’ recalls Dr Panesar. ‘The idea was to shake up the dominant thinking at the time, which saw most of the investments going into big pipes, treatment plants and other types of infrastructure.’

This idea resonated with the team at CSE, who were increasingly worried about the shape of a new ‘end open defaecation’ campaign which was being launched in India. They saw that SFDs could be a powerful tool in their efforts to broaden the narrative of sanitation the country.

Toilets are not the same as sanitation

In October 2014 the Prime Minister of India launched the Swachh Bharat (Clean India) Mission, an ambitious campaign which aimed to make India open defaecation free (ODF) by 2019 through the construction of 100 million new toilets in urban and rural areas. While no one questioned the urgent need to provide access to dignified sanitation to all Indians, and to reduce the health and environmental risks of faecal contamination, sanitation experts knew that a narrow focus on toilets was likely to mean the further neglect of everything that needs to happen after they are flushed.

Toilets are not the same as sanitation. They are simply the first link in the ‘sanitation chain’ which begins with the containment of human excrement, and extends through emptying, transport, treatment, and disposal or re-use. All the toilets in the world will not protect humans and the natural environment from disease and pollution unless what comes out of them is safely managed at each stage of this chain.

Sadly, this was not the case in much of India. According to the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme, in 2014 only 11 per cent of Indian households had toilets connected to sewer systems and only 34 per cent had access to sanitation services that could be considered safely managed. Under the Swachh Bharat Mission, most of the newly constructed toilets would empty into septic tanks or latrines, not sewers. As CSE’s research had shown, the design, construction and maintenance of such on-site containment systems was poorly regulated. This meant that no one really knew whether such tanks contained faecal matter safely, how often (if at all) they were emptied, how the faecal sludge was transported, how much of it was treated, and what happened to the parts that were not.

SFDs offer a new way of looking at an old problem

When Suresh Kumar Rohilla, the head of the water programme at CSE, first saw an SFD he was quickly sold on the concept. ‘We had been using a traditional mix of statistics, diagrams and photographs in our advocacy work with decision-makers,’ he explains. ‘We saw right away that SFDs would allow us to present the complicated picture of urban sanitation in a single image.’

Under the auspices of the SFD Promotion Initiative, CSE began to popularise SFDs in large and medium-sized cities across India. It started by focusing on 11 of the cities which it had already exhaustively researched for the Excreta Matters study. By plugging existing data into the SFD graphic generator, which is freely available on the Promotion Initiative’s website, the team at CSE was able to rapidly visualise the fragmented sanitation flows through these cities. This added new potency to the findings of their earlier research.

‘When we sit at the traffic signal every day, we orient on the green and red lights to know when it is safe to proceed, and when it is dangerous,’ says Rohilla. SFDs mirror the same logic, he explains. ‘When you see a lot of red, you understand immediately that there are serious problems.’

A valuable addition to city sanitation planning

The GIZ-implemented ‘Support to National Urban Sanitation Policy’ project – part of Indo-German bilateral cooperation – also saw the potential of the SFDs. GIZ and CSE had been working together since 2014 to develop the capacity of officials in 35 small and medium cities in three states to prepare City Sanitation Plans – prerequisites for accessing central government financing for sanitation projects.

GIZ and CSE selected six of these cities – two each in Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Telengana – to develop SFDs from scratch as part of their City Sanitation Plans. The SFDs provided them with a sound basis upon which to plan investments. Today, all six of these cities are among the leaders in effective faecal sludge management in India. The city of Siddipet, for example, has installed a faecal sludge treatment plant, while Karim Nagar has begun the co-treatment of faecal sludge and sewage at the city’s sewage treatment plant.

GIZ has since supported the development of further SFDs in partner cities such as Coimbatore and Rishikesh. ‘We’ve found that SFDs are an excellent way to get conversations going,’ says Rahul Sharma, a technical advisor with the GIZ Smart Cities project who has worked with SFDs. ‘The Indian scenario is characterised by too much raw data, too little analysis, and very little centralisation of data. By bringing data into this structured format, SFDs provide a basis for discussion and ultimately for evidence-based decision making.’

SFDs influence national policy and broaden the narrative around sanitation

The SFD graphics and reports which began emerging from cities across India turned into powerful advocacy tools for those pushing for investments in on-site sanitation solutions. CSE technical staff began using SFDs widely in workshops, at conferences and in meetings with central government officials.

The visualisations were compelling, and caught people’s attention. They even reached the Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, who pored over an SFD with Bill Gates during a meeting at which they discussed India’s progress in improving urban sanitation.

Before too long, it was clear that the lens for viewing sanitation challenges was widening. In 2017 the Government of India adopted a National Faecal Sludge Management Policy – the highest-level acknowledgment thus far that it would be impossible for India to reach its commitments under the Sustainable Development Goals without attention to on-site sanitation systems.

In 2018, the Swachh Bharat Mission officially broadened its mandate beyond the elimination of open defecation to also include the ‘safe containment, processing and disposal of faecal sludge and septage’ (a formulation that came to be known as ODF++).

Soon thereafter, indicators related to faecal sludge management were incorporated into Swachh Survekshan, the official system for monitoring and ranking cities according to their progress on sanitation. This provided even more incentive for cities and states to plan for and introduce interventions aimed at improving on-site sanitation. There were signs of a virtuous cycle: more attention and the breakdown of long-held taboos were fuelling more action, which in turn led to greater willingness to tackle the issues ‘behind the toilet’.

From ‘controlled explosions’ to official endorsement

Suresh Kumar Rohilla remembers that, back in 2014, his biggest concern about SFDs was not the ‘controlled explosions’ they would provoke, but rather their name: ‘The language was not very diplomatic,’ he recalls. ‘“Excreta” is a highly technical word that only a few people understand, while the SFDs use a word that everyone understands, but no one wants to use,’ he laughs. ‘Were policymakers in India ready for this?’

It turns out that they were. Since SFDs first came to India, more than 400 cities have used them to map out their sanitation situations. Roughly 100 of the graphics and reports have been peer reviewed and published in the SFD Promotion Initiative’s global repository.

According to Rohilla, it is not uncommon to see SFD graphics displayed prominently in the offices of mayors and municipal commissioners. ‘More than 450 cities across India have taken up interventions addressing on-site waste management,’ he explains. ‘Local officials are keen to show that they are moving forward.’

SFDs have been officially endorsed in a central government technical advisory, issued by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, as a tool which cities can use in developing their sanitation plans. The government is also making funding available to cities to support the planning process itself, which means that development of SFDs can now be undertaken using public resources.

A global seal of excellence

Through its support for the SFD Promotion Initiative, BMZ has made a major contribution to broadening the focus beyond toilets, sewers and infrastructure to the sustainable, decentralised sanitation solutions that the world’s poorest people depend on.

‘The global SFD repository has been very important for ensuring the quality and comparability of SFDs from city to city,’ says Rohilla. ‘Governments can point to the fact that they have a peer reviewed SFD when they apply to lending institutions for sanitation investments.’ This seal of excellence will continue to be important in the years to come as the transition towards inclusive, climate-friendly sanitation systems gathers pace.

Karen Birdsall

March 2022