An important step towards better patient care

Health professionals need access to real-time data systems to enable them to make better-informed decisions about the care they provide to their patients. In the first project of its kind in Malawi, a German development cooperation programme with co-financing from Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is helping to get health facilities in Dedza district connected to the national digital network. How does this work?

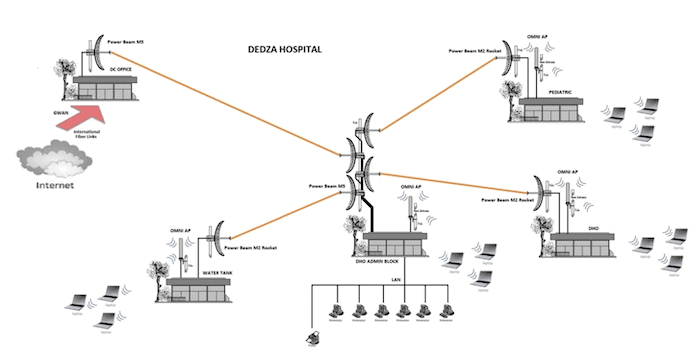

Dedza District hospital is a typical single storey, red brick building just off the main north-south M1 highway in central Malawi. It serves a population of around 730,000 and deals with referrals from 34 health facilities in the area. What distinguishes it from similar hospitals in the country is a plethora of antennae that has recently sprung up on the roof, linking it to the country’s digital network.

You might think that digital technology would not be high on the list of priorities in a health system that has to make do, and somehow is making do, with very little staff and cash: Recently, no fewer than 63 babies were delivered at Dedza District hospital in just one weekend – with only three nurses on duty. Malawi has only one doctor to 80,000 patients (compared to around 400-600 in Europe) and some hospitals do not even have running water. But then: how do you improve care without an accurate picture of what is happening in your health facilities?

Keeping up with technology can be a struggle in resource-poor settings

In recent years Information Technology has generally advanced at a much faster pace than institutional evolution to cope with the advance of IT. This is especially so in the health sector, says Dr Simon Ndira, a technical adviser on health information systems for Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ)‘s Malawi German Health Programme (MGHP). It is also difficult to secure sufficient funding for IT developments in resource-scarce health services. The good news, says Dr Ndira, is that there is a now a greater global awareness of the importance of IT – partly due to the fact that the Sustainable Development Goals are evidence-based and driven by data.

Malawi has been operating the Health Management Information System DHIS2 for some time, but up until now, there has been no system in place to let frontline health workers make use of the valuable information it generates. While they must record patient data on paper, which is then forwarded to the district level and eventually entered into the Ministry’s central data repository, up until now health workers at the facilities have had no access to the aggregated data and could not use it to improve the quality of care. IT infrastructure and connectivity at health centres and district hospitals could change this. And this is what’s now happening in the pioneering Dedza project.

The Government of Malawi has with funding from the Chinese Government established a Government Wide Area Network (GWAN) that goes as far as the District Commissioner´s Office in each district. Health, education and agriculture and other institutions in each of the 28 districts need to find partners to support the extension of the GWAN to the ‘last mile’ and set up a functional local area network to make internet freely accessible to all staff. The German programme has supported the extension to the District Health Officer´s Office and Dedza District Hospital to bring frontline staff online and empower them to make better decisions.

‘Patients don’t come to be counted, they come because they are sick.’

Last year the Ministry of Health instructed that all e-health-related initiatives should be managed by a newly-established Quality Management Directorate (QMD) within the Ministry and managed by doctors rather than statisticians. A new unit for e-health has also been established under QMD: shifts that have made Malawi’s e-health initiatives more relevant at the point of care. Dr Andrew Likaka, the QMD Director says: ‘Patients are not coming to be counted – they don’t care about statistics. They come because they are sick. As a medical doctor, my first priority is to serve the patient – not collect data. Data need to improve patient care – that’s what we want to achieve.’

According to Kai Straehler-Pohl, head of the Malawi German Health Programme (MGHP), reliable IT infrastructure and cost-effective internet uptime at health facility level are essential for two reasons: Firstly, individual clinicians can access the data they need to diagnose and treat specific patients; and secondly, health facility teams can use the aggregate DHIS2 data to develop and monitor evidence-based quality improvement plans. ‘Our project is working on both, but connectivity is the precondition, so we start with that.’

What are the aims of MGHP and how have these been implemented?

MGHP is working to strengthen health systems in the target districts of Lilongwe, Dedza, Mchinji and Ntcheu with a focus on maternal and newborn health. The programme started in February 2017 and is currently planned to run until July 2020. ‘We believe that data is critical in monitoring health outcomes for mothers and babies,’ says Dr Ndira. To provide staff with the data they need for decision-making, MGHP has introduced an e-register platform for patient management at point of care. ‘For this to work’, says Dr Ndira, ‘connectivity is key.‘

Dedza is the first of what MGHP hopes will be many facilities to be connected, providing a architectural blueprint for future national connectivity in the health sector. The programme has a dedicated budget of 120,000 Euros, to expand the initiative to 10 health facilities in each of the four areas where it is working – making it 40 in total. ‘It seems like a simple task, but it is not,’ says Dr Ndira. ‘To extend the network across the country will be a matter of cost and effort,’ he adds: ‘This is going to be a journey.’

At a higher level, digital sustainability will depend on government leadership and long-term investment to make sure that resources are properly coordinated and aligned, so as to avoid fragmentation and duplication of efforts by partners helping to link the last mile in different areas. MGHP in collaboration with other health development partners is supporting the Government of Malawi in these efforts.

The impact of better connectivity

In a small office at Dedza District Hospital, HMIS Officer Jumphani Kalua and his assistant Veronica Madengere are busy updating the central repository DHIS2 with statistical data from the hospital, which are in turn used by the Quality Improvement Support Teams and Work Improvement Teams to make informed decisions about improving care. Their work is supported by ICT Officer Tumbikani Munthali, who maintains the computers and ensures they remain connected to the network. The effects of better connectivity in Dedza have been immediately apparent, says Dr Ndira. Reporting rates have greatly improved – from around 60% to 100% – and the information is being used to improve the quality of care.

‘Now we don’t have to have to wait for information from HMIS people to come to us; we can use the GWAN to access it ourselves,’ says Misha Stande the District Medical Officer for Dedza. Every maternal and neonatal death, for example, is now audited immediately to see what went wrong. ‘It is really helping because you can check any time – in the ward, in the office – and it is easy to share the data.’ Health workers also feel more ownership of the processes.

What have been the major challenges?

At first there were challenges, says Misha Stande, largely because of frequent power outages which affected connectivity. But things have improved. To manage the frequent power outages MGHP has begun to design systems that use off-grid solutions such as solar power and hybrid systems charged by a combination of grid and solar energy. Upload times of 18 to 24 hours have also been designed into the system to prevent data loss during outages. Many health workers in Malawi are not digitally or computer-literate, so it is important that they are properly trained. With this in mind, MGHP conducted training on data use and demand last year before connection to GWAN.

Sometimes, however, such as when 63 babies were delivered in one weekend with only three nurses on duty, Dr Stande says there is no time to enter the data, so the nurses use paper records and then input the data later – creating extra work for them.

We live in a world dependent on information

In a resource-poor setting, there are sometimes difficult decisions to be made between buying a computer or basic equipment such as surgical gloves, between three nurses having to deliver 63 babies in one weekend at Dedza hospital, and the need to fill in digital forms. However, Dr Stande says: ‘Data is really important and comes in everywhere, so even if it is expensive – in the long run it’s a price we have to pay. There is nothing we do in this world that can be done without information.’

She believes that initiatives such as that supported by MGHP in Dedza can also help to address some of challenges the hospital faces from lack of resources. An e-Register, for example, will reduce paper costs, freeing up money that can be used in other areas.

Currently the government has an IT strategy, but no digital health policy, so the next step will be to try to develop one, says Dr Likaka, the QMD Director in the Ministry of Health: ‘We need to change mindsets and to understand that digital health is not about IT, but about patient-focused systems, designed to help health workers improve the quality of care. The last mile project Germany supports in Dedza is a pioneering step in the right direction.’

Ruth Evans

September 2019