One year after a massive earthquake hit Nepal, hundreds of health facilities still need to be rebuilt. A detailed engineering assessment of damaged health facilities is helping those involved with reconstruction efforts to plan their work more efficiently.

The 7.8-magnitude earthquake which struck Nepal on April 25 of last year inflicted massive damage upon the country’s health infrastructure. In the 14 districts most affected by the earthquake and its aftershocks, some 400 health posts, two dozen primary health care clinics and a pair of hospitals were completely or partially destroyed.

A year later, reconstruction efforts are underway at more than 300 facilities, but the pace of progress has been painfully slow. Only 42 facilities have been completely rebuilt and many patients are still being treated in tents or under open skies.

Operating in an information vacuum

Manjeet Raj Pandey, the construction manager with the International Medical Corps in Nepal, knows firsthand why it can take a long time to get started on actual rebuilding. His organisation is supporting the Ministry of Health of Nepal to rebuild 22 health posts in five different districts. Late last year when International Medical Corps was allocated its first set of health posts, in Gorkha District, Pandey and his colleagues had virtually no idea what awaited them there – or even how to find the facilities and the people responsible for them.

They ended up making multiple, time-consuming trips back and forth between Kathmandu and Gorkha District to meet with the health workers in charge of each health post, to complete topographical and geotechnical surveys of each site, and to organise and conduct community consultations. They also had to gather all sorts of logistical information: Was water available at the site? Could they procure building supplies such as wood, sand and bricks somewhere close by? Would they be able to hire skilled and unskilled labourers in each area?

With better background information, many of these tasks could have been completed significantly faster. But a year ago there was no comprehensive, up-to-date information available about Nepal’s health infrastructure. International Medical Corps and other support organisations were basically operating in an information vacuum.

A detailed engineering assessment generates better information

Six months later, the picture is radically different. Thanks to information generated through a detailed engineering assessment of 784 health facilities, conducted late last year with the support of Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) – via the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) – and the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), Pandey and his colleagues were able to organise their most recent site assessments, in Nuwakot District, much more efficiently.

‘After consulting the data from the engineering assessment, we had a good idea of the condition of the sites ahead of time. We could make contact with the person in charge at each site and arrange the community meeting before we headed out from Kathmandu,’ Pandey explains. ‘This meant that when we arrived at the health posts, we could focus on the things we needed to focus on.’ Recently, they completed pre-construction assessments for nine new health posts in one single 10-day trip from Kathmandu.

Clarifying a confused picture

The need for detailed engineering information became clear about two months after the earthquake as offers of reconstruction assistance were pouring in to the Ministry of Health’s Policy Planning and International Cooperation Division.

The information which had been gathered through an official Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) the month after the earthquake turned out not to be reliable enough to allow the Ministry to direct assistance where it was needed most. ‘There was lots of confusion. We had to amend many agreements with organisations because we weren’t aware of the actual situation on the ground,’ explains Sagar Dahal, who coordinated the engineering assessment on behalf of the Ministry.

Most of the damage reports had been collected over the telephone and health workers had widely varying ideas of how to classify damage. What was ‘partially damaged’ to one might be ‘functional’ to another. ‘Sometimes the PDNA would report that a facility was totally collapsed, but the organisation would get there and find that it was only partially collapsed,’ says Dahal. ‘There was an urgent need to get first-hand information that was verified at field level.’

Bringing together engineering and information technology

The detailed engineering assessment was the brainchild of group of advisors from the GIZ-implemented Nepali-German Health Sector Support Programme (HSSP) and the DFID-supported Nepal Health Sector Support Programme (NHSSP) who began working together as an informal team following a meeting of development partners shortly after the earthquake.

It was a complementary partnership: DFID brought a detailed understanding of the health sector infrastructure, having worked closely with the Ministry in this area for more than a decade, while GIZ had valuable experience with information management in health systems. ‘Working together is always better than working alone,’ says Deepak Paudel, a DFID Nepal Health Adviser, reflecting back on the intense collaboration between the two development partners. ‘We joined together two different areas of expertise, both of which were needed for the project to work.’

Using the GPS coordinates for health facilities which were already available in the Health Infrastructure Information System which NHSSP was developing in cooperation with the Ministry, the GIZ-DFID team was able to plan out the most efficient routes for pairs of engineers to visit every health facility in the 14 most-affected districts.

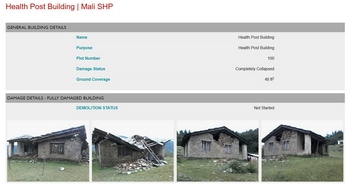

Between September and December 2015, three dozen trained engineers inspected 17 hospitals, 41 primary health care clinics and 726 health posts, capturing their findings on tablets using a specially-designed questionnaire. They assessed earthquake-related damage in accordance with the standard seismic vulnerability guidelines produced by the Department of Urban Development and Building Construction and also checked the status of all medical equipment. In addition, they gathered basic information about the facility, including the type and quality of access road, ‘lifelines’ (e.g. water, electricity, telephone, internet), proximity to markets, land ownership status, and local availability of building supplies.

A publicly-available resource

The findings of the detailed engineering assessment have been publicly available on the website of the Nepal Health Sector Programme (www.nhsp.org.np) since January of this year. Each facility has its own entry, complete with GPS coordinates, contact information for the facility head, photographs, floor plans showing the location of damages, and all other information gathered during the site visit.

‘Many of the international organisations who are supporting us with pre-fabricated construction use this information to select facilities and this makes life easier for my team who review proposals,’ explains Mahendra Shrestha, Chief of the Policy Planning and International Cooperation Division at the Ministry. ‘By putting it on the website, people now see if a facility is damaged or not and then come to us with proposals.’

World Vision International is one such organisation. Rather than sending out their own teams to do rapid assessments of potential sites, as they did previously, they are now able to consult the information available online. ‘The data provides a good starting point for us to identify places where there is a need for completely new constructions,’ explains Roji Alex, the Roving Shelter and Infrastructure Manager for World Vision.

A comprehensive basis for future planning

The relatively simple information-gathering tool developed in the aftermath of last year’s earthquake is proving to have far-reaching benefits. According to the Ministry of Health’s Mahendra Shrestha, the main added value became clear when the country’s National Reconstruction Authority asked his Ministry to submit a detailed recovery plan for the health sector in all 31 districts affected by the earthquake. ‘We used the results of the engineering assessment to design the recovery framework and to estimate the resources that would be required,’ he explains. These estimates are now much more accurate than those generated through the Post-Disaster Needs Assessment, which reported 24 percent more damage (in terms of number of fully or partially damaged facilities) than the site-based inspections ultimately revealed.

‘For us as a development organization,’ says Paul Rueckert, the Chief Technical Advisor of the Nepali-German Health Sector Support Programme, ‘it was important not only to contribute to the immediate response to the earthquake, but also to find ways to strengthen the health system as a whole. We knew that the foreign medical teams would eventually leave and the task of reconstruction and building a resilient health system would remain.’

Karen Birdsall

April 2016